On a recent flight from Utah to Washington DC I made a new friend when I told him that I was going to give a presentation on how our planet was infinitely bountiful. Most people are shocked when you tell them that resources will be fine but that there’re not enough people. They’ve been told all their lives that we live on a finite planet with finite resources and that if life left is “unchecked” life will cease to exist. We had a great discussion for four hours, during which he made an important observation: products today don’t seem like they last as long as they used to. Grandma’s refrigerator ran for 30 years while refrigerators today seem to have a much shorter lifespan.

His point is worthy of consideration, but there’s another important factor to consider. refrigerators that last forever miss out on the benefits of creative-destruction innovation. The Harvard economist Joseph Schumpeter noted this as one of the key characteristics of capitalism. Older refrigerators often have a reputation for lasting longer, but the facts suggest that tradeoffs are at play. Pre-1990s models were built with simpler, more durable components, like robust compressors, and could last 20-30 years with minimal maintenance. However, they were less energy-efficient, consuming 2-3 times more electricity than modern units. Newer refrigerators, designed under stricter energy regulations (e.g., EPA’s Energy Star standards), use advanced insulation, variable-speed compressors, and eco-friendly refrigerants, but these complex systems can be prone to failures, especially in electronic controls or sensors. The average lifespan for modern units is 10-15 years, though high-end brands like Sub-Zero or Bosch can match the durability of older model.

Alex Tabarrok notes that

Recent research from the Association of Home Appliance Manufacturers trade group shows that in 2010 most appliances lasted from 11 to 16 years. By 2019, those numbers had dropped, to a range of nine to 14 years. (In some cases, such as for gas ranges and dryers, the lifespans actually increased.)

The 15 percent decline is partially explained by government regulation.

Every appliance service technician I spoke to — each with decades of experience repairing machines from multiple brands — immediately blamed federal regulations for water and energy efficiency for most frustrations with modern appliances.

…The main culprit is the set of efficiency standards for water and energy use for all cooking, refrigeration, and cleaning appliances.

When prices rise faster than hourly wages, the culprit is almost always government interference—through excessive regulation, burdensome taxation, or inflationary policies. Unlike entrepreneurs, government officials don’t face the discipline of profit and loss. They spend without accountability and impose costs without consequences.

Government is the primary force behind deabundance—the systematic erosion of affordability and progress.

Entrepreneurs, by contrast, thrive by creating more with less. They compete to lower prices, improve quality, and serve more people. In the free market, profit is earned by solving problems, cutting costs, and accelerating learning. But when government breaks the feedback loop between cost and consequence, abundance begins to unravel.

Contrary to what Marxist university professors and progressive politicians claim, businesses like to lower prices not raise them. Lower prices attract more customers, increase sales, and generate higher profits through scale. Each additional unit produced creates an opportunity to learn, improve, and reduce costs. These learning curves are the engine of progress. Lower costs enable even lower prices, which expand markets further.

This is the virtuous upward spiral of free enterprise: knowledge compounding, prices falling, wealth expanding. The entrepreneur who learns fastest wins—not by hoarding, but by sharing, scaling, and serving. The company that learns the fastest is usually the most profitable. Elon Musk’s companies are not just building cars or rockets—they are climbing learning curves at light speed. He understands that the true source of wealth is not money or matter, but discovering and sharing valuable new knowledge.

Let’s go back to Grandma’s refrigerator. In 1956 you could buy a new Frigidaire for $470. Unskilled workers at the time were earning around $1.00 per hour putting the time price at 470 hours. Today you can buy one at Home Depot for $578 but unskilled workers are earning closer to $17.50 an hour, putting the time price at 33 hours. For the time it took to earn the money to buy one refrigerator in 1956 you get over 14 today. Even if they might not last as long as Grandma’s refrigerator, we’re still much better off.

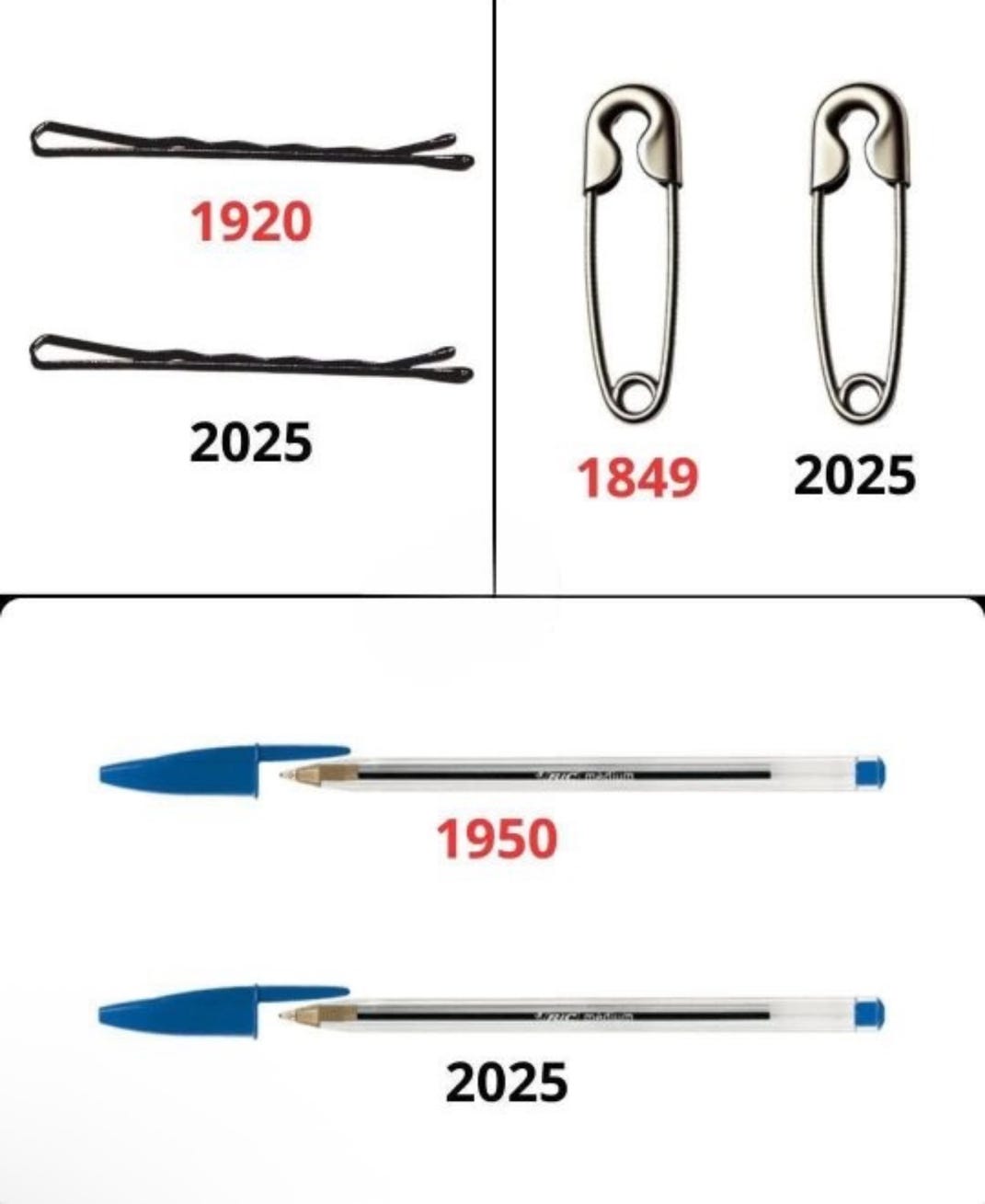

On the other hand, if a product has reached the apex of perfection, then you really do want it to last forever. Fingernail clippers may be one such example. I could be wrong but I don’t know how to improve them. I’ve also had the same ones for 20 plus years.

Here are a few other examples:

But cars are a different story. My first car was a 1956 Chevy Bel Air. Back then, you could buy a brand-new one with the base V-8 engine for around $2,443. Even with factory options and accessories, it typically stayed under $3,000. At $1.00 an hour that car would cost an unskilled worker 3,000 hours of time.

Fast forward to 2025 and unskilled compensation is around $17.50 an hour. At that rate, the equivalent money price of the Bel Air would be about $52,500—roughly the price of a new Tesla Model Y, currently the most popular car in the U.S.

So here’s the question: how many 1956 Chevys would I have to give you in exchange for your 2025 Tesla?

Having personally experienced both, I wouldn’t trade a single Tesla for a thousand Bel Airs. As iconic as the ‘56 Chevy is, it simply doesn’t compare to what a Tesla delivers. In fact, if someone offered me a brand-new ‘56 Chevy today, I’d consider it more of a liability than an asset. The Tesla far surpasses the old Chevy in every category: reliability, safety, comfort, efficiency, and especially maintenance. And nothing even comes close to the magic of Tesla’s Full Self-Driving feature.

Some products are perfect. They work great and are extremely affordable but most others can still be improved. We don’t want them to last forever.

Tip of the Hat: Shane McPartland

Learn more about our infinitely bountiful planet at superabundance.com. We explain and give hundreds of examples why more people with freedom means much more resource abundances for everyone in our book, Superabundance, available at Amazon.

Gale Pooley is a Senior Fellow at the Discovery Institute, an Adjunct Scholar at the Cato Institute, and a board member at Human Progress.

Interesting article, although let's not forget the hedonic treadmill! Having a certain level of technology will be cool at first, then we'll take it for granted.

It always amazes me when I analyze how good we have things compared to times past in both technology and capability.