Energy is essential to creating abundance. Whether it’s used to organize and move atoms or to store and transmit information, economic development depends on energy. While energy can be sourced in many forms and measured in various units—such as BTUs or joules—the kilowatt-hour (kWh) is likely to become the standard unit of comparison. A kilowatt-hour represents the energy delivered by one kilowatt (1,000 watts) of power sustained over one hour. Though not an SI unit (Système International d'Unités), one kWh is equivalent to 3.6 megajoules (MJ) in SI terms.

Energy density varies dramatically across different sources. A standard 42-gallon barrel of crude oil contains approximately 5.8 million British thermal units (MBtu), or about 1,700 kilowatt-hours (kWh) of energy—though the exact amount depends on the grade of oil. In contrast, a single pound of uranium fuel can produce roughly 17,000 kWh of electricity. At the other end of the spectrum, a teaspoon of sugar contains just 0.0000000189 kWh. These comparisons highlight the vast differences in how much energy can be stored in different forms of matter.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) tracks average electricity prices over time. The chart below shows the U.S. average nominal price per kWh from 1980 to the present—rising from about 6 cents in 1980 to 17.6 cents today.

To convert the money price into a time price, we compared the blue-collar hourly compensation rate for each year, indexing the 1980 rate to 1. The result shows that the time required to purchase a kilowatt-hour of electricity has declined by 26.6 percent since 1980.

Another way to understand electricity prices is to ask: how many kilowatt-hours (kWh) can you buy with one hour of work? This chart illustrates that relationship. In 1980, an hour of blue-collar labor could buy 152 kWh; today, it buys 207 kWh—a 36 percent increase in energy abundance.

The regression line plotted on the chart suggests a steady gain of about two additional kilowatt-hours per year for the same amount of work. Although time prices have spiked over the past three years, the long-term trend points toward continued growth in abundance.

If you started your first job as an unskilled worker in 1980 and “upskilled” to a blue-collar job by 2024, your time price for electricity would have dropped by 67.3 percent. For the time it took to earn enough to buy 100 kWh in 1980, you could now purchase 306 kWh—representing a 206 percent increase in electricity abundance.

What will AI do for the abundance of electricity? Human imagination and ingenuity are amplified and energized with AI. Expect even greater abundance if we have more people with the freedom to innovate energy.

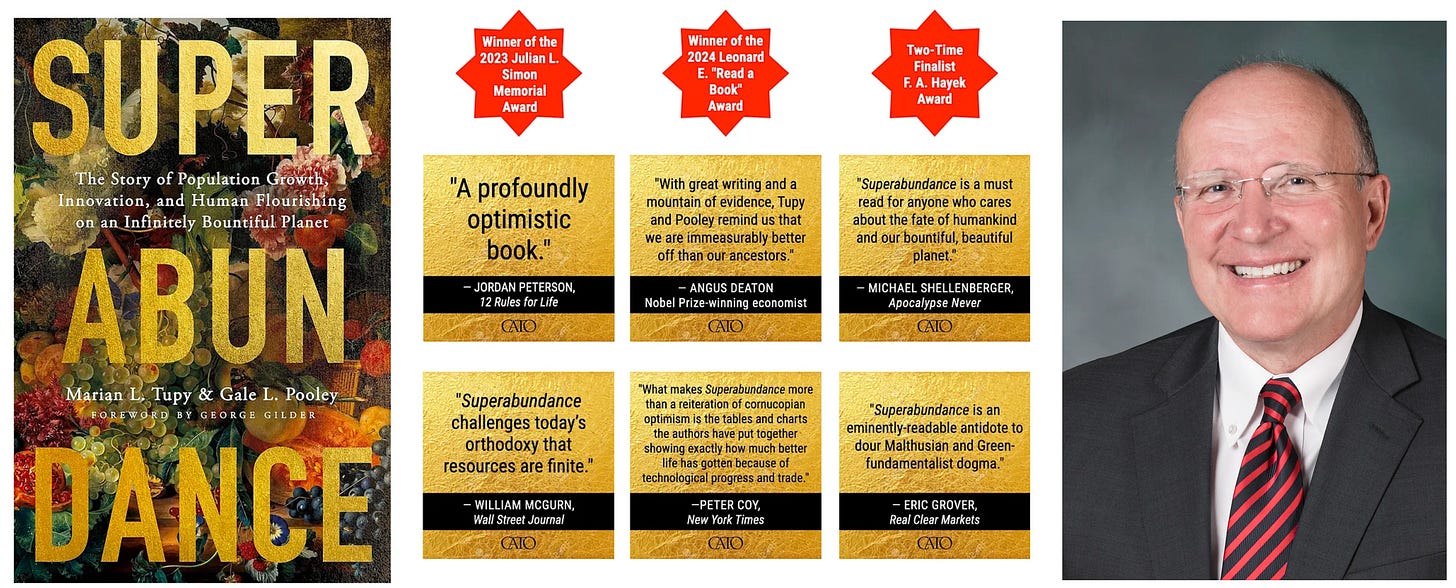

Learn more about our infinitely bountiful planet at superabundance.com. We explain and give hundreds of examples why more people with freedom means much more resource abundances for everyone in our book, Superabundance, available at Amazon.

Gale Pooley is a Senior Fellow at the Discovery Institute, an Adjunct Scholar at the Cato Institute, and a board member at Human Progress.

I found a more pesssimistic view looking at price indices for electricity(both the PCE and CPI), which show an over 3.5x increase in price from 1980-2024. And thus little improvement in affordability. Do you know anything about how these are constructed and what may explain the differing results?

How much of the recent increase in nominal energy costs is due to California and a few others states? Here in Arizona, I know that my electricity bill has not gone up by anything like that amount. Perhaps that has something to do with the big nuclear plant not far away?