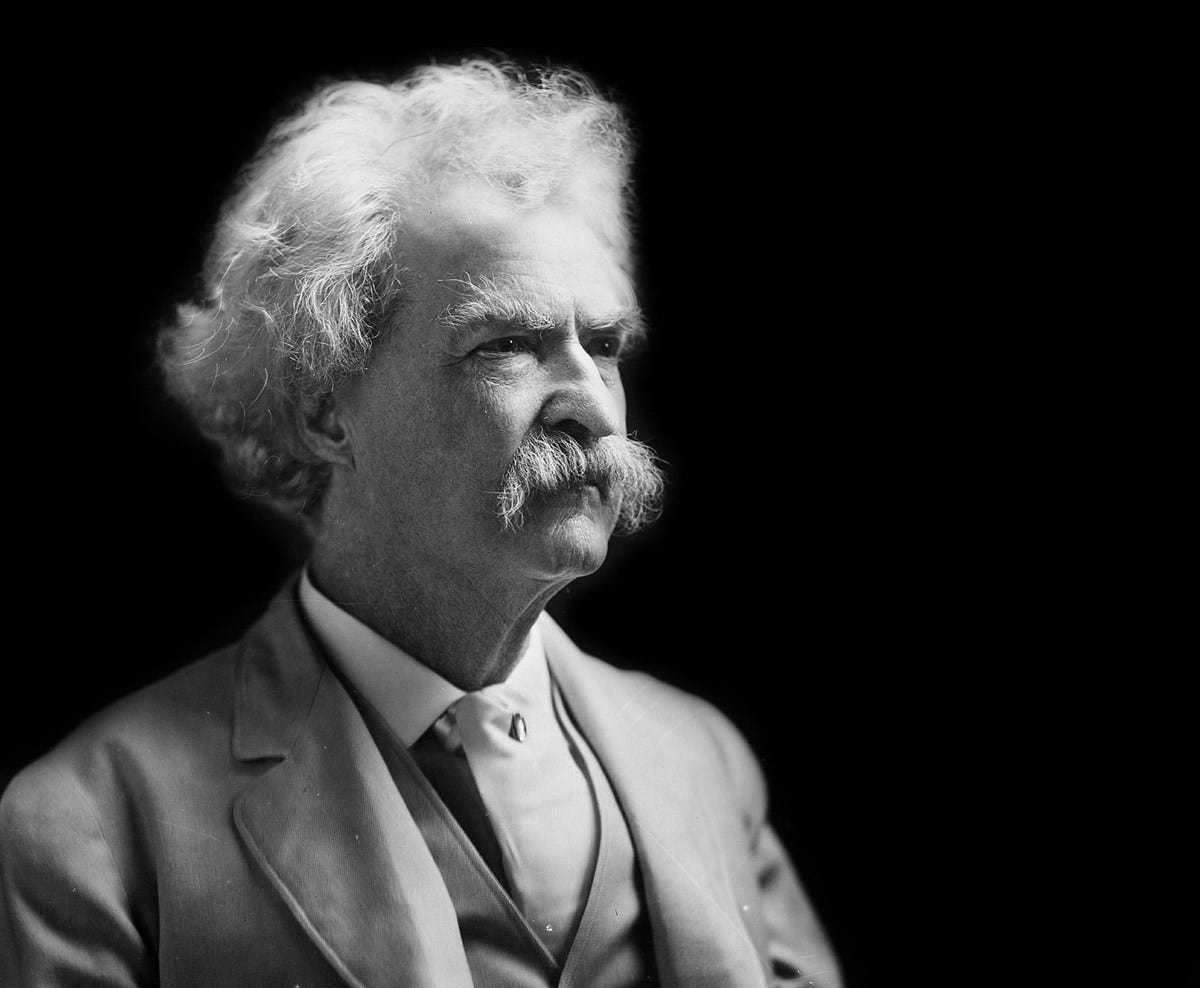

Mark Twain Explains Time Prices

The amount of the wages has got nothing to do with it. The thing is, how much can you buy with your wages?—that’s the idea.

Inspired by Kody Jensen at FEE.org

Kody Jensen found a great reference about time prices from Mark Twain in his story, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court. The story follows a 19th century American who is bonked on the head and goes back in time to the Dark Ages.

The Yankee debates a blacksmith on trade and protectionism:

“In your country, brother, what is the wage of a master bailiff, master hind, carter, shepherd, swineherd?”

“Twenty-five milrays a day; that is to say, a quarter of a cent.”

The smith’s face beamed with joy. He said:

“With us they are allowed the double of it!”

The Yankee is forced to admit that wages in the smith’s country are generally higher. However, he comes back with some questions of his own.

“What do you pay a pound for salt?”

“A hundred milrays.”

“We pay forty. What do you pay for beef and mutton—when you buy it?” That was a neat hit; it made the color come.

“It varieth somewhat, but not much; one may say seventy-five milrays the pound.”

“We pay thirty-three.”

The time prices tell the story:

While the blacksmith’s wages were twice as high, salt was 150 percent higher and beef and mutton were 127 percent higher. This made the time price of salt 25 percent higher and beef and mutton 14 percent higher for the blacksmith relative to the Yankee.

From the Yankee’s perspective, wages were 50 percent lower, but salt was 60 percent lower and beef and mutton were 56 percent lower. This made the time price of salt 20 percent lower and beef and mutton 12 percent lower for the Yankee relative to the blacksmith.

The blacksmith continued to argue that since his wages were twice as high, that he must be better off. The Yankee responds:

“Yes-yes, I don’t deny that at all. But that’s got nothing to do with it; the amount of the wages in mere coins, with meaningless names attached to them to know them by, has got nothing to do with it. The thing is, how much can you buy with your wages?—that’s the idea.

Mark Twain was not only a great storyteller, he also understood that we buy things with money, but we pay for them with time. Time prices are the true prices.

Tip of the hat to Ron Baker ron@verasage.com

You can learn more about these economic facts and ideas in our new book, Superabundance, available at Amazon. Jordan Peterson calls it a “profoundly optimistic book.”

Gale Pooley is a Senior Fellow at the Discovery Institute and a board member at Human Progress.

That is amazing!😂😂😂