On a recent flight to Washington, D.C. to make a presentation at the Cato Institute on the new Beginner’s Guide to Superabundance to 5th-12th grade teachers and administrators, I had the unexpected pleasure of rewatching Disney’s A Bug’s Life. I had forgotten what a truly brilliant story it is.

Emmanuel Rincón wrote a nice review of the film back in 2022, which inspires my own analysis.

In the current age where human ingenuity continually multiplies our abundance, making resources ever more plentiful, there’s no ethical or moral justification for a sprawling bureaucracy that consumes without creating. This astute insight shines through in Pixar’s gem, a story that vividly illustrates how innovation and free collaboration can transform scarcity into superabundance.

If you’ve overlooked A Bug’s Life, you’ve bypassed one of the most uplifting films ever crafted. This animated triumph ranks among the most profound celebrations of libertarian principles on screen, championing the creative spark that drives human progress. It's perhaps no coincidence the film debuted in that innovative year of 1998, the same year as the founding of Google and PayPal, and the launch of the Apple iMac.

In our current era, it’s rare to encounter a movie that boldly affirms positive ideals while exposing the flaws of totalitarian control. Over recent decades, Hollywood’s giants have largely abandoned narratives of heroic innovators and role models, opting instead for tales fixated on victims’ plight under oppressors—stories that wallow in suffering without delivering real hope, merely perpetuating a mindset of scarcity and grievance.

Yet A Bug’s Life breaks this mold. While it features Hopper—the menacing grasshopper—as one of animation’s most chilling villains, it counters with Flik, the relentless inventor who experiments tirelessly with new ideas and ultimately liberates the ant colony from Hopper’s exploitative domination.

Some media outlets have mistakenly labeled the film a critique of “capitalism,” interpreting it as a saga of class conflict among downtrodden workers, but this view misses the mark entirely. True free-market systems foster voluntary cooperation without force; they honor private property as the foundation of prosperity. In the movie, the ants defend their hard-earned harvest—their private output—against grasshopper invaders who seize it through coercion, mirroring not capitalism but the expropriation tactics of socialist states. This isn’t an attack on markets; it’s a defense of creators against those who plunder, highlighting how genuine abundance arises from protected innovation, not mandated redistribution.

Fascinatingly, Flik—driven solely by a vision of freeing his community from oppression—faces constant rejection from fellow ants for defying the grasshoppers’ authority. This echoes our modern societies, where growing deference to bloated governments and their elite administrators stifles the very ingenuity that could multiply our collective wealth. Still, Flik’s unyielding belief in deliverance propels him forward, embodying the human potential to turn time and effort into exponential gains.

Hopper: Archetype of the Scarcity Mindset in Socialism

Hopper, the story’s antagonist, personifies the collectivist tyrants who’ve plagued the past century—figures like Stalin, Mao, Castro, Chávez, Pol Pot, or Hitler—who viewed ordinary people as mere fodder to sustain an elite class. In Hopper’s zero-sum worldview, ants are disposable laborers obligated to feed the grasshoppers, much like socialist systems where citizens toil to enrich bureaucrats. What passes for “wealth redistribution” is often just appropriation, leaving producers with scraps while the powerful hoard the bounty—a far cry from the abundance that flourishes when knowledge and ideas are freely shared.

In a revealing exchange, Hopper lectures the ant princess: “It’s a bug-eat-bug world out there, princess. One of those Circle of Life kind of things. Now let me tell you how things are supposed to work: The sun grows the food, the ants pick the food, the grasshoppers eat the food…”

Intimidated by his threats, the princess submits, as Hopper maintains dominance through fear and enforced obedience, akin to the coercive styles of real-world dictators.

When his own grasshoppers question the need to bully the ants further for provisions, Hopper snaps back: “You let one ant stand up to us, then they all might stand up! Those puny little ants outnumber us a hundred to one and if they ever figure that out there goes our way of life! It’s not about food, it’s about keeping those ants in line.”

Hopper intuitively grasps that sustaining fear is key; should the ants awaken to their own power, the grasshoppers’ idle privileges would vanish, forcing them to innovate and labor for their own sustenance—revealing the fragility of systems built on extraction rather than creation.

Flik’s Vision: Igniting Abundance Through Ingenuity

Like his colony mates, Flik is a modest ant, lacking the physical might to overpower Hopper’s gang, but he’s brimming with bold ideas and boundless courage—qualities that echo humanity’s greatest resource: our capacity to invent and adapt.

Venturing far to rally aid, Flik enlists a quirky circus troupe of bugs and returns to thwart Hopper’s perpetual enslavement scheme. Though his first strategy falters, Flik’s resilience sparks inspiration across the colony, demonstrating how one innovator’s persistence can multiply outcomes for all.

As tensions peak, Hopper bellows at Flik: “You piece of dirt! No, I’m wrong. You’re lower than dirt. You’re an ant! Let this be a lesson to all you ants! Ideas are very dangerous things! You are mindless, soil-shoving losers, put on this Earth to serve us!”

Flik retorts with clarity: “You’re wrong, Hopper. Ants are not meant to serve grasshoppers. I’ve seen these ants do great things. And year after year, they somehow manage to pick food for themselves and you. So who is the weaker species? Ants don’t serve grasshoppers. It’s you who need us. We’re a lot stronger than you say we are. And you know it, don’t you?”

Flik’s words unsettle the grasshoppers, emboldening the ants to advance. Hopper rallies his forces, but the ants, now aware of their superior numbers and inherent strength, overrun their oppressors. The princess seals the victory: “You see, Hopper, nature has a certain order. The ants gather the food, the ants keep the food, and the grasshoppers leave!”

In essence, the ants required only a spark of courage to claim their freedom, with Flik providing the innovative catalyst to dismantle the grasshopper regime. Flik’s ingenuity turned potential scarcity into shared prosperity.

A Bug’s Life delivers a profoundly hopeful message, one we must embrace by following Flik’s lead: there’s no moral basis for exhaustive toil merely to sustain bureaucrats. True wealth belongs to those who generate it through creativity and exchange, not to rulers who impose unjust laws and wield force to intimidate. As our history shows, when people are free to innovate, abundance doesn’t just grow—it compounds, doubling every generation or so, benefiting everyone thanks to the infinite bounty of human knowledge.

300th Post

This is my 300th post. It is also our four-year anniversary. Substack has been a great platform to share facts and interesting stories about innovation and human flourishing. Thank you for reading and making comments. I really appreciate all of your faith and support. Please take a look at our archives. We’ve done some really fun articles and even surprised ourselves. A special thanks to Benjamin Hare for his excellent proofreading skills. I encourage everyone to create a Substack and try to write and publish something every week. Your thinking will definitely improve. If you have a specific product or service that you would like to see analyzed, please send a message. We’ll try our best to accommodate. We’re also up to 930 subscribers. Our goal is to hit 1,000 this year. If you think our articles are valuable please share with your friends.

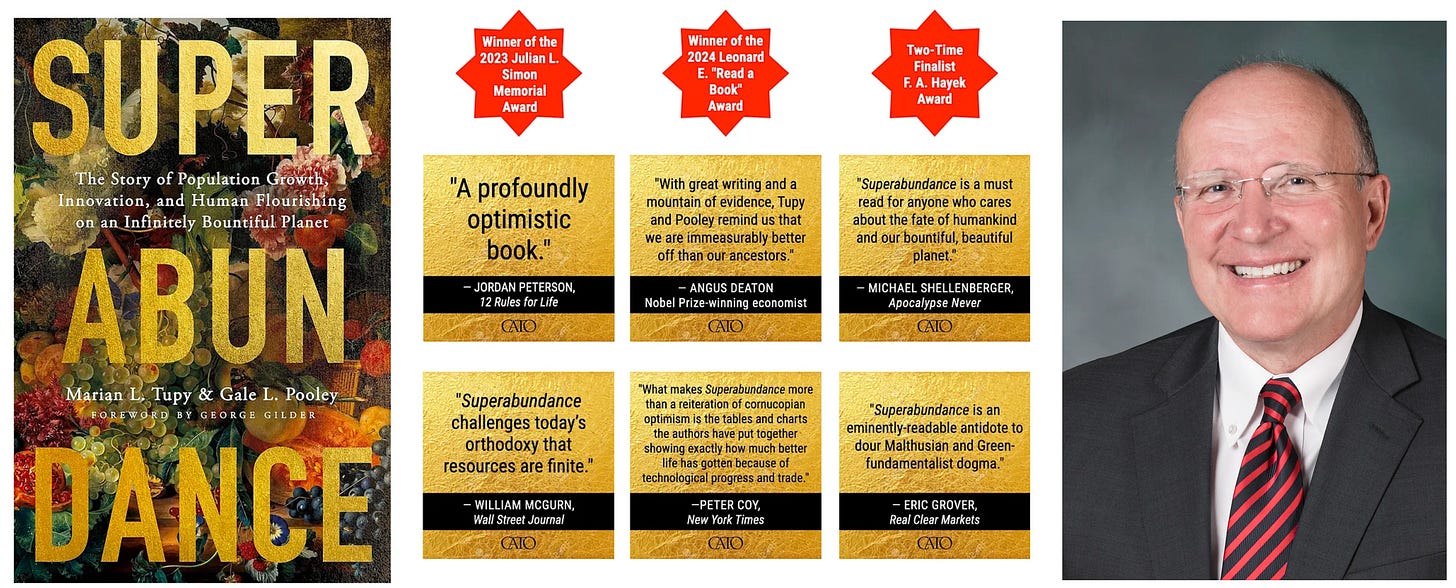

Learn more about our infinitely bountiful planet at superabundance.com. We explain and give hundreds of examples why more people with freedom means much more resource abundances for everyone in our book, Superabundance, available at Amazon.

Gale Pooley is a Senior Fellow at the Discovery Institute, an Adjunct Scholar at the Cato Institute, and a board member at Human Progress.